As more families buy their holiday gifts online rather than in-store, it’s increasingly warehouse and transportation workers whose labor makes gift-giving possible. The CEOs of ecommerce behemoths have already increased their wealth by tens of billions of dollars during the pandemic, and will rake in billions more over the holiday season. Meanwhile, traditional retail jobs trail far behind their pre-COVID numbers. And many individuals—including retail and warehousing workers—struggle to stay afloat in the aftermath of the COVID recession. Even before the pandemic, women and people of color fared worst in these sectors.

When you buy from an ecommerce corporation like Amazon, much of the resulting work happens in fulfillment centers and is categorized as “warehousing and storage,” a subsector of the “transportation and warehousing” sector. A traditional brick-and-mortar store, on the other hand, is categorized by the Bureau of Labor Statistics as part of the “retail trade” sector and includes stores selling clothing, personal care goods, electronics and appliances, and hobby and sporting goods.

Last month, retail trade jobs declined by 20,000, while transportation and warehousing jobs grew by 50,000. Retail’s drop in 20,000 hides considerable gender differences. In November, women’s retail jobs were still 191,200 below pre-COVID levels, while men’s retail jobs are 15,400 above what they were in February 2020.

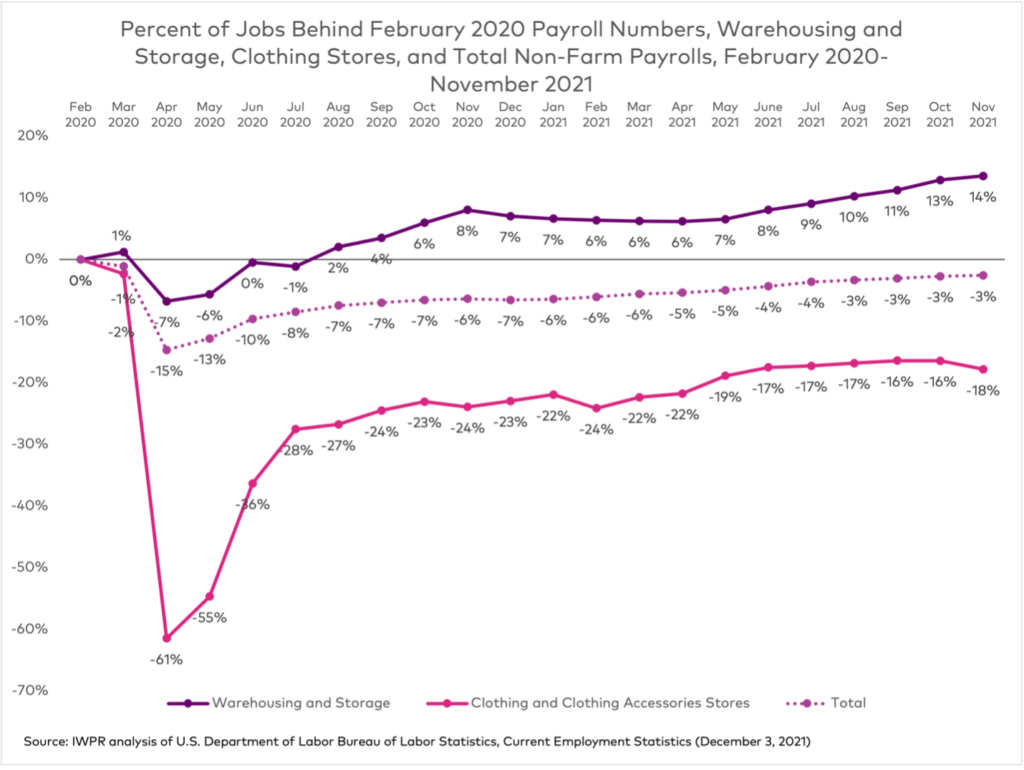

There are also disparities between within retail subsectors. Retail jobs overall are almost (98.9 percent) back to pre-COVID-19 payroll employment, but clothing/clothing accessories store jobs are still down 18.0 percent compared to February 2020. Warehousing and storage jobs, on the other hand, are well above pre-COVID numbers (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Warehousing jobs have recovered— and then some— while clothing retail jobs lag far behind

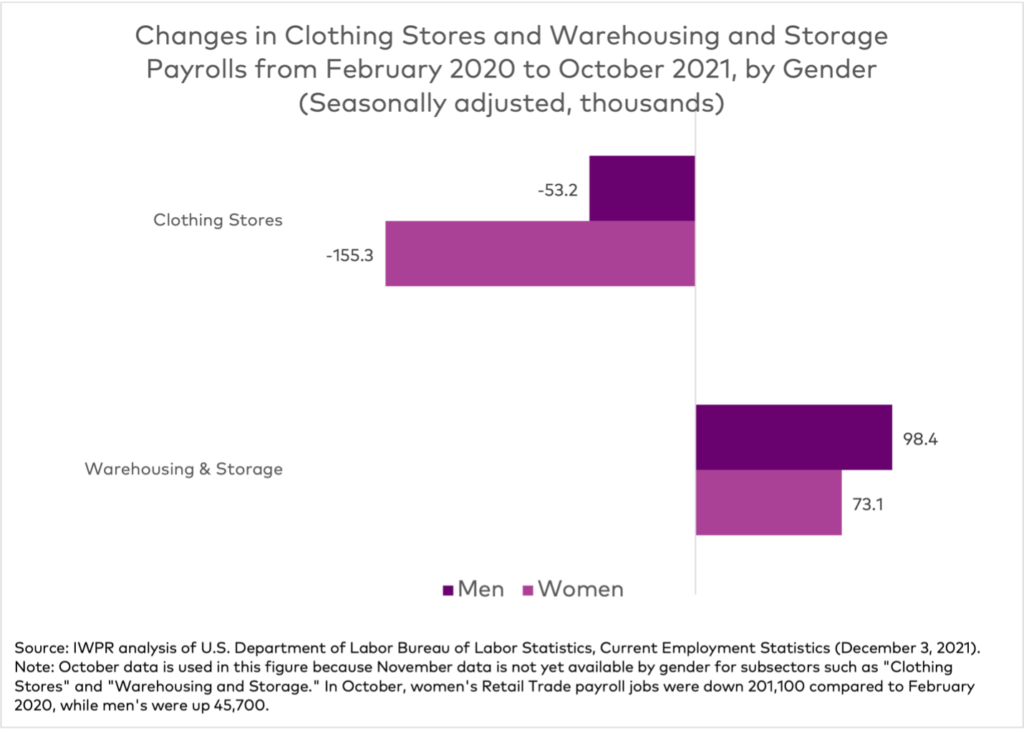

As with other parts of the economy, understanding that there is a high level of gender segregation is key for understanding the state of the COVID recovery for those who work in retail and warehousing. Women are 48.9 percent of all workers on payroll in retail, but make up 71.5 percent of clothing store workers—not much changed from their share of these jobs pre-COVID. In November, clothing store jobs, which were hit especially hard by the pandemic, were still more than 200,000 below their level in February 2020.

Warehousing and storage, on the other hand, is overwhelmingly men-dominated. However, women have seen an increase in transportation and warehousing employment over the last few months, growing to 32.0 percent of workers in the subsector (up from 30.7 percent in February 2020). It’s the only sector where—compared to February 2020—women’s share of all jobs has grown by more than 1 percentage point.

As IWPR research has shown, the COVID-19 “she-cession” has largely been the effect of strong occupational segregation. Now the recovery shows some cracks in the most severe areas of job segregation as more women have moved into transportation and warehousing. Unfortunately, additional recruitment of women in warehousing doesn’t make up for loss of women in other retail jobs.

Figure 2. Clothing store jobs are still more than 200,000 behind pre-COVID numbers, with greater losses for women, while warehousing jobs have grown across genders

While both retail and warehousing/storage sectors have below-average median earnings and tend to be low-quality in terms of benefits, working conditions, and harassment (more from IWPR), the men-dominated warehousing and storage sector does pay more than the retail trade sector. On average, nonsupervisory employees in retail trade make $18.86 an hour and work 30.9 hours a week. In 2020, these workers had median annual earnings between $25,740 and $31,660 depending on their occupation. In comparison, nonsupervisory employees in warehousing and storage make $20.81 an hour and work 39.2 hours a week. In 2020, they had median annual earnings between $32,680 and $38,180 depending on their occupation.

So what do we take away from all this? First, the holiday season is propped up on millions of people’s underpaid labor—this is true especially for women and people of color. It does not matter whether that labor happens in a brick-and-mortar store or in a warehouse. Many of these workers face difficulties organizing and securing the kinds of protections and advantages afforded by a union, while corporate executives in these sectors continue to rapidly accumulate wealth. Second, deep “she-cession” losses and an uneven job recovery mean that this holiday season will be particularly difficult for women. Due to occupational segregation, women are overrepresented in the low-paying point-of-sale jobs that took the hardest hit during the pandemic and underrepresented in higher-paying warehousing jobs that will only continue to grow.

As we approach another pandemic holiday season, we must double-down on the fight to reduce occupational segregation, increase wages and job quality in both retail and warehousing sectors, and advocate for strong social safety nets like those in the Build Back Better plan. These measures will ensure all workers can access a better quality of life and the opportunity to thrive—not just during the holidays, but all year round.