This year Mom’s Equal Pay Day is on September 8th. This date marks the point where moms finally catch up to what dads earned in the previous year. In other words, moms must work 20 months to make what dads made in 12 months. The “average”* mom earned just $0.63 cents for every dollar earned by the “average”* father in 2020 — $22,000 less per year to spend, build up savings, and contribute to retirement funds. These data are based on the 2021 Current Population Survey (CPS-ASEC), the latest available data.

The wage gap narrows when considering full-time year-round workers instead of all workers. Mothers working full-time year-round earned $0.73 cents for every dollar fathers earned, on average. This is substantially worse than the reported earnings ratio between all women and all men who worked full-time year-round in 2020, in which women made $0.83 for every dollar earned by men. However, excluding part-time or part-year workers undercounts mothers who are unable to work full-time because of their unpaid care burdens or because full-time year-round work is simply not available. IWPR research found that, on an average day, women in the United States spend two more hours a day than men (37 percent more time) on unpaid household and care work. Due to these unequal care burdens, women are more likely to work part-time, and this is especially true for mothers. Nationally, in 2020, 61.3 percent of mothers work full-time year-round compared to 80.0 percent of fathers (IWPR analysis).

The inequality in earnings and time in paid work is found in every state. The maps below show the gap in earnings and earnings ratio for all states. To complete a state-level analysis, data are from the 5-year American Community Survey 2016-2020. Use the navigation button to view data for all mothers and fathers with earnings and full-time year-round (FTYR) working mothers and fathers.

The worst states for mothers, with the largest wage gap between mothers and fathers, are:

- Utah (earning 42.7 percent of what fathers made),

- Idaho (49.9 percent), and

- Louisiana (51.2 percent)

Mothers earned the least, on average, in:

- Idaho ($25,312, which is $25,385 less per year than the average dad),

- Utah ($26,399, which is $35,451 less per year than the average dad), and

- Mississippi ($27,337, which is $20,633 less per year than the average dad)

The best states for mothers, with the smallest pay gaps between moms and dads, are:

- Vermont (earning 72.0 percent of what fathers made),

- Maine (67.4 percent), and

- South Dakota (66.0 percent).

Moms had the highest earnings in:

- the District of Columbia ($61,484),

- Maryland ($46,387), and

- Massachusetts ($44,872)

In more than half of the states (29 states), Moms earned 60.0 percent or less than what dads earned.

These data are for all workers; to view data for FTYR workers, please use the navigation button labeled “View FTYR Workers”.

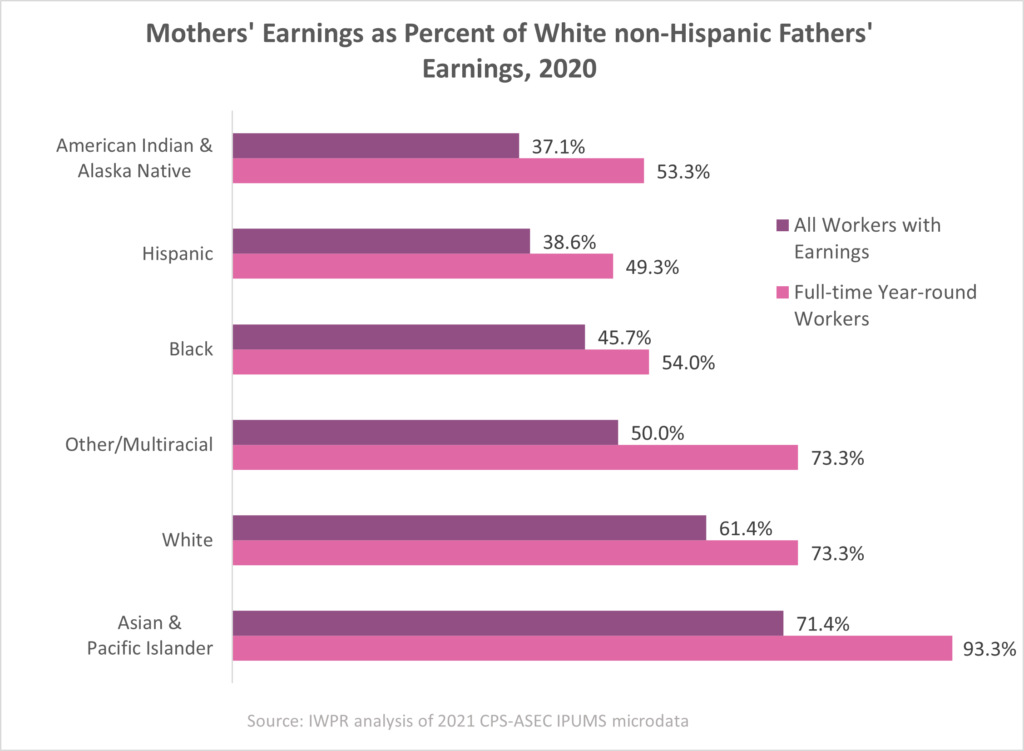

The motherhood wage gap is widest for women of color, yet they are particularly likely to be the main or sole breadwinner in their families. Pay gaps between moms and dads are even more significant when analyzed across racial and ethnic groups, compared to White, non-Hispanic fathers. View the chart below to see the full breakdown of the earnings ratio between moms and dads for each racial or ethnic group.

- American Indian & Alaska Native mothers make $0.37 cents for every dollar a White, non-Hispanic father makes.

- Hispanic mothers make $0.39 cents for every dollar a White, non-Hispanic father makes.

- Black mothers make $0.46 cents for every dollar a White, non-Hispanic father makes.

These pay gaps are the result of the long history of policies that count out or devalue working moms.

Moms are facing a dual-squeeze: lower pay while managing high child care costs. This is especially burdensome for single mothers, Black and Hispanic mothers, and mothers in college. A significant obstacle to finding quality, affordable child care is the fact that the child care sector is lagging substantially behind the broader economic recovery. This slow recovery is not surprising due to the low earnings of many child care center workers.

The nation’s failure to implement policies that encourage and support parents in the workforce explains one-third of the decrease in women’s labor force participation (when comparing the US with other high-income countries). Research has shown that policies supporting affordable childcare are effective in encouraging mothers to enter the workforce – since Washington, D.C. implemented two years of free universal public preschool in 2009, the percentage of mothers with young children working in the labor force increased by 12 percent. IWPR’s research shows that universal pre-K would save families $17 billion in out-of-pocket expenses–which would allow both parents to pursue economic opportunities.

Working moms are also at a disadvantage due to the “motherhood penalty”, defined as “a wage penalty associated with becoming a mother or adding new children to a family that cannot be explained by other factors, such as seniority or education.” This penalty arises out of biases that assume working moms are less committed to their jobs due to their status as mothers, along with the lack of policies that support working moms like paid family and medical leave, paid sick days, and access to affordable, high-quality childcare.

These biases affect not only working moms, but all working women who are held to standards that reinforce women’s role as primary caretakers and men as breadwinners. Even if one is not pregnant, the possibility of pregnancy is still perceived in the workplace to reflect one’s commitment to their job.

Amidst the overturning of Roe v. Wade, it is important to note the connection between access to abortion and economic security. IWPR’s Reproductive Rights Index — a report which ranks each state according to its policies around reproductive rights and healthcare–illuminates this connection. States which ranked among the lowest in terms of women’s access to reproductive rights and healthcare, such as Idaho, Utah, and Mississippi, also have larger wage gaps between mothers and fathers. These states are also less likely to have policies to support working moms, like paid family and medical leave or paid sick leave. This means that they’re not only denying pregnant people the freedom to make their own decisions about pregnancy and childbirth, but are also failing women and families once children are born.

It’s critical that legislators, on both state and federal levels, prioritize working toward equal pay and supporting working mothers. Our analysis highlights how mothers do not have a monolithic experience due to factors such as race and ethnicity. For this reason, it is vital that legislation is created through an intersectional lens to ensure equity among all groups of mothers. This must include a full range of policy solutions that include paid family and medical leave, paid sick time, and other comprehensive work supports, as well as increased minimum wage and schedule control while considering factors such as the role race and background play in women’s lives. It also must include policies that support access to a full range of comprehensive reproductive health care services, including abortion, as well as to affordable, high-quality child care.

* Average at the median of earnings.