Almost four in ten unemployed women have now been out of work long-term, for 27 weeks or longer. Between February 2020 and January 2021, the number of unemployed women almost doubled (from 2.7 to 4.8 million), but the number of long-term unemployed more than tripled (from 491,000 to 1.9 million). While the overall rate of unemployment fell slightly in January (to 6.3%), the share of unemployed women who were unemployed for more than half a year increased (to 38.9%). Added to those who are formally unemployed are over 2 million women who left the labor force since February 2020.

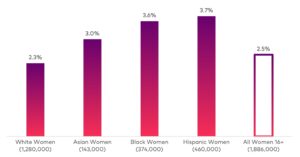

Racial inequalities persist amongst the long term unemployed. Unemployment of 27 weeks or more is highest for Hispanic, Black, and Asian women, with rates 64, 58, and 33 percent higher than White women, respectively (calculated based on Figure 1).

Figure 1: Percent of White, Black, and Hispanic Women 16 Years and Older in the Labor Force who were Employed for 27 Weeks or Longer

Source: IWPR Analysis of US BLS Current Population Survey Data (accessed 2/11/21)

The longer a worker has been out of a job, the harder it can be to break back in—with significant effects on lifetime earnings. This is a phenomenon called labor force scarring, in which time spent out of work is related to negative labor market experiences in the future, like lower pay, higher unemployment, and reduced life chances (including negative impacts on mental health). According to a study by the Center for American Progress, at the national median annual wage level ($34,248) one year out of the labor force at age 30 costs an individual nearly $110k over a lifetime.

Another study found that nonemployment was correlated with a 35–40 percent decrease in earnings after ten years—largely due to a higher likelihood of unemployment down the road. The negative repercussions are most severe for individuals at the highest and lowest ends of the earnings spectrum.

This means that the aftermath of the COVID-19 recession will continue long after its formal end— a situation which calls for a strong COVID relief package, as well as a long-term commitment to effective and accessible workforce development initiatives and living wages for all. As the racial and gender disparities in employment and unemployment show, a recovery policy needs address the underlying racial injustice in order to be truly effective.