By Mia Ogorchock, graphic by Nic Martinez

In the buzz surrounding the World Cup triumph of the U.S. Women’s National Team (USWNT), “equal pay” has become a rallying cry, not just for the team, but for their fans. In March of this year, the USWNT filed a gender-discrimination suit against the United States Soccer Federation, Inc., citing unequal pay, training, and travel conditions, compared with the men’s team, despite bringing in higher revenue–and winning more games. Their fight is part of a bigger movement of women across industries advocating for better pay and safer workplaces, while confronting inadequate or outdated economic policies that shape how we live and work.

Women still make about 80.5 cents to every male dollar per year and the gap is even larger for women of color. Based on current trends, IWPR projects that women overall will not achieve pay equity until 2059, while Black women will wait one century (until 2119) and Hispanic women will wait more than two centuries (until 2224) until they reach equity with White men’s earnings.

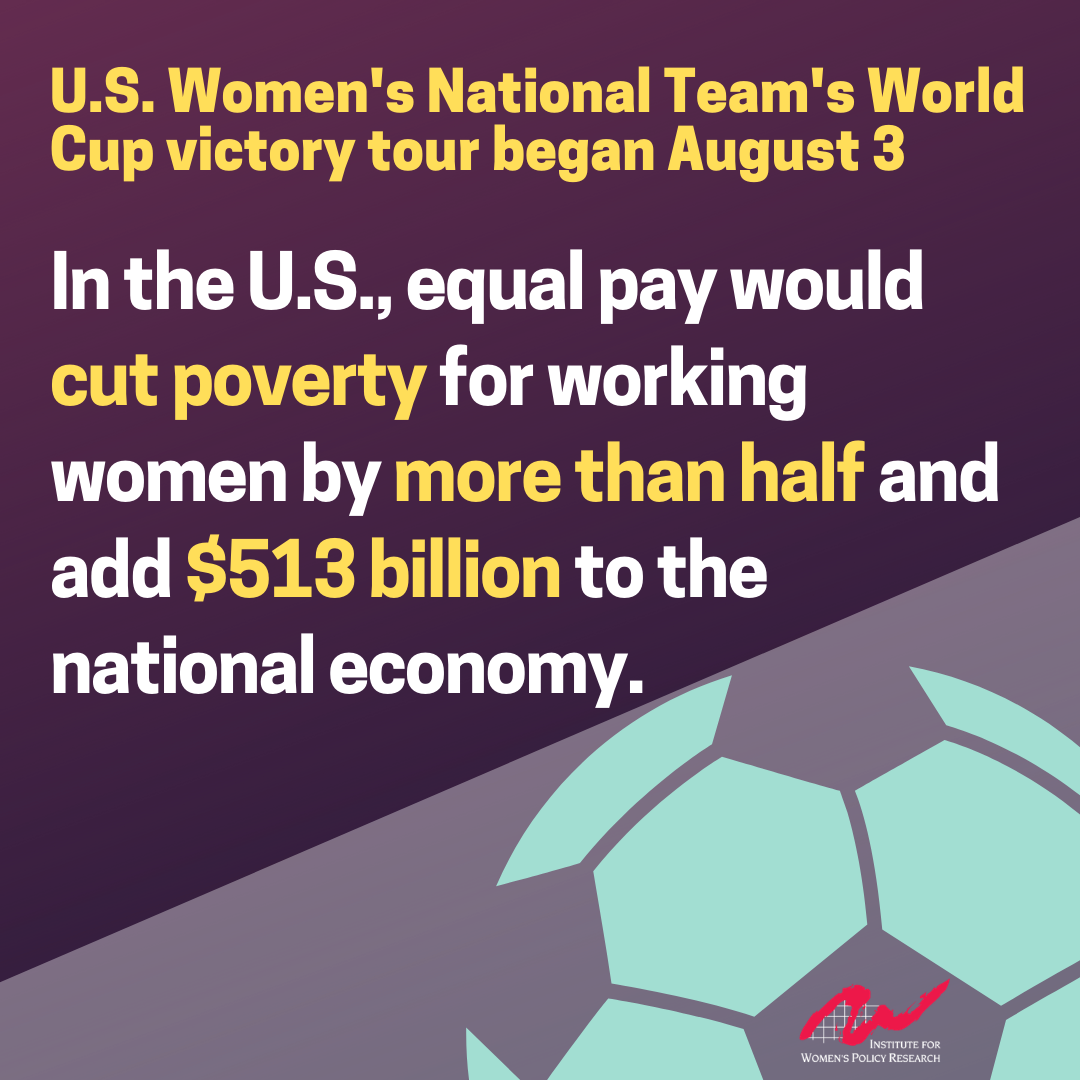

As the USWNT begins their victory tour around the country, here is a look at the gender-equity policies that would not only narrow the gender wage gap, but would reconfigure the economy to work better for everyone.

Valuing Women’s Work

The call for equal pay for the USWNT—and for all women—has been echoed in op-eds in major news outlets and invoked by 2020 candidates, many of whom have made it a centerpiece to their platforms. For good reason: while there was significant progress in narrowing the wage gap in the 1980s and 1990s as more women entered the workforce and gained entry to many fields and jobs they had previously been excluded from, progress over the last two decades stalled. Women today still earn less than men in nearly every single occupation for which there is enough data to calculate the wage gap.

Researchers find that over half of the wage gap can be explained by occupational segregation: women and men tend to work in different jobs and the jobs men tend to do pay more. The segregation is stark—four in ten (39 percent) working women work in female-dominated occupations and nearly half of men (48 percent) work in male-dominated occupations—and widespread, from staggering wage gaps in top-paying fields to greater concentration in jobs that pay poverty-level wages.

This segregation also affects how the economy values “women’s work.” Low-wage, female-dominated jobs pay less than male-dominated low-wage work, even when women’s jobs are very similar in requirements for education, skills, and stamina: janitors (two-thirds men) make $12.13 per hour, while maids and housekeepers (nearly 90 percent women) make $9.94 per hour. Furthermore, those who perform low-wage women’s work are about twice as likely to have a college degree than workers in male-dominated occupations—yet earn less. As jobs of the future become more digitalized, the trends are concerning: despite being more likely to work with computers and digital media than men, women face a 41 percent earnings gap on returns for their digital skills.

With half of U.S. families having a female breadwinner, the undervaluation of women’s work has real consequences for families, communities, and the economy as a whole. Pay parity would cut poverty in half for working families and add nearly half a trillion dollars in additional wage and salary income to the U.S. economy.

The disconnect between women’s skills and contributions and the gender gap in earnings is paralleled by the USWNT: while the team has qualified for (and won) multiple World Cups, the men’s team famously failed to qualify for the 2018 World Cup. The men’s team is paid more for the games they win in the tournament, despite bringing in less revenue than the USWNT.

Improving Access to Paid Leave and Child Care Would Help Narrow the Wage Gap

In addition to ensuring that women have access to good jobs and high-paying fields, strengthening women’s attachment to the labor force is also key to narrowing the wage gap. We know from a large body of research that improving access to paid leave and affordable child care improves women’s labor force participation, which can in turn improve their earnings.

The earnings penalties for those who take time out of the labor force are high and increasing. For women, who still disproportionately shoulder the burden of care in their families, the effect can be a huge blow to the pocketbook: women who took just one year off during a 15-year period earned 39 percent less than women who did not take any time away from the paid labor force. That is why the gender wage gap as traditionally reported understates pay inequality: women make just half of what men make over a 15-year period

Many working families and single mothers lack access to paid family leave or childcare. Here too, we see parallels with the USWNT’s story: Jessica McDonald, the only mother on the US Women’s National team, has cited issues with paying for child care, including working several jobs at a time to pay for expensive childcare for her son. McDonald’s—and other working mothers’—ability to pursue a fulfilling job and provide for her family relies on being able to access and afford child care. Too many women are unable to do so: women are nine in ten of the workers who cut back paid work to care for children or family members.

As the experiences of the USWNT remind us, equal pay is not just about being paid the same—although that would help. Fighting for pay equality is about fighting for things like access to good jobs, investment in training and supports such as paid leave, child care, and other gender-equity policies that would improve the economy and reduce inequality for everyone.