by Cynthia Hess, Ph.D., and Asha DuMonthier

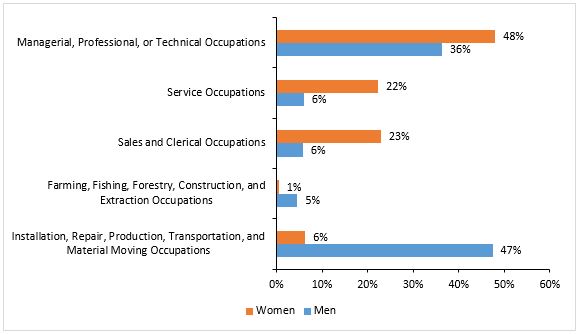

Women and men enter job training programs with similar goals in mind—they want to expand their skill set, increase their earnings, and support their families. However, there is a gender divide in the occupational areas for which women and men receive training, which contributes to to inequalities in men and women’s earnings. Women are more likely to receive training in managerial, technical, and professional occupations, as well as in service and sales and clerical occupations (Figure 1). Men, however, are much more likely than women to receive training in male-dominated occupations like construction and transportation, which tend to have higher earnings than female-dominated jobs. This gender segregation in training programs closely resembles patterns in the labor market as a whole, where women are 72.2 percent of office and administrative support workers, while men are 96.5 percent of installation, maintenance, and repair workers, and more than 97 percent of all construction and extraction workers.

Figure 1. Occupational Breakdown of Training for Adult Exiters, from April 2013 to March 2014

Source: IWPR compilation of data from Social Policy Research Associates 2015, Table III-21.

Gender segregation in job training programs has important implications for women’s long-term economic security. Data for adults who finished training programs funded by the Workforce Investment Act (WIA) between April 2013 and March 2014 show that while women were the majority of those who received intensive and training services (51 percent, Table II-10) and were, on average, in programs of longer duration than men (Table II-18), their average earnings after receiving WIA services were lower than men’s. In the fourth quarter after finishing adult programs, women who exited programs between July 2012 and June 2013 earned $5,296 compared with $7,188 for men (Table II-31). (Published data do not provide information on earnings prior to receiving WIA services and include all exiters, not just those with full-time earnings.)

Women earn less after completing job training programs in part because female-dominated occupations (occupations where women are more than 75 percent of the workforce) pay less than traditionally male occupations (occupations where men are more than 75 percent of the workforce). In a study of Perkins-funded CTE programs using data from the U.S. Department of Education and Bureau of Labor Statistics, women made up over 80 percent of participants in 2010 in postsecondary “Human Services” courses, which prepare students for low-paying service jobs such as Child Care Provider ($9.34 per hour on average) and Cosmetologist ($10.85 on average). In contrast, women were less than 10 percent of participants in “Architecture and Construction” courses, which train students for higher-paying jobs like Electrician ($23.71 per hour on average).

Multiple forces contribute to gender segregation in job training programs. One study found that counseling services may influence women’s decisions to pursue traditional female-dominated career paths. While many women in the study said that they were not interested in nontraditional skills, the number who reported that they were interested was greater than the number who were referred to nontraditional training. What is more, many of the women surveyed said that the career advice they were given did not include information on the likely wages and benefits of different occupations; had they known this information, they might have pursued nontraditional training.

Women pursuing career paths in male-dominated fields may also experience difficulties as a result of hostile work cultures or outright discrimination. In a recent IWPR poll of about 80 financial social workers, the most common explanation given for women’s low share of good-paying jobs in male-dominated fields was discrimination and a lack of a welcoming work and training environments. The scarcity of women in higher-skilled, male-dominated occupations may make women in those training programs and employment settings feel isolated and increase their chances of exposure to harassment and discrimination.

Because women are the primary or co-breadwinner in half of U.S. families with children, women’s lower earnings after completing training programs have serious consequences for families’ economic security. Encouraging women to pursue nontraditional fields through counseling and fostering welcoming and non-discriminatory environments in male-dominated fields are important steps to ending gender segregation in programs and increasing women’s opportunities to secure jobs that will provide economic stability for themselves and their families.

Cynthia Hess, Ph.D., is Associate Director of Research at the Institute for Women’s Policy Research. Asha DuMonthier is a Mariam K. Chamberlain Fellow for Women and Public Policy at the Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

To view more of IWPR’s research, visit IWPR.org