Publicly funded child care assistance helps many low-income parents afford child care while earning a postsecondary credential that can lead to long-lasting economic security. States have flexibility in setting eligibility requirements for receiving subsidies funded by the federal Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) program (Adams et al. 2014; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2016). Compared with other states, Washington imposes unusually strict requirements, including work requirements and degree limitations, for parents in job training and education programs who wish to receive child care assistance (Eckerson et al. 2016). Changes to Washington State’s eligibility rules for child care assistance receipt would help parents attain credentials that lead to stable, high-quality jobs with family-sustaining wages. Increasing postsecondary attainment among low-income parents could also reduce poverty over the long term, reduce reliance on public benefit programs, help employers meet the demand for skilled workers, and strengthen the state’s economy.

Nearly One Quarter of Washington’s Community and Technical College Students are Raising Children

Nearly 5 million college students in the United States are raising children while they go to school. In the Far West region, 22 percent of all undergraduates—more than 700,000 college students—are student parents (Noll, Reichlin, and Gault 2017).[1] In Washington State, nearly 46,300 community and technical college (CTC) students—representing 23 percent of all CTC students in the state—are parents of dependent children, according to data from the Washington State Board of Community and Technical Colleges (IWPR 2017a).[2]–[3] A large portion of Washington’s student parents (41 percent) are raising their children and pursuing college without the support of a spouse or partner. Women are more likely than men to be parenting while in school (27 percent of women in postsecondary education are raising children, compared with 18 percent of men) and more than three quarters (77 percent) of single student parents in Washington are mothers (IWPR 2017a).

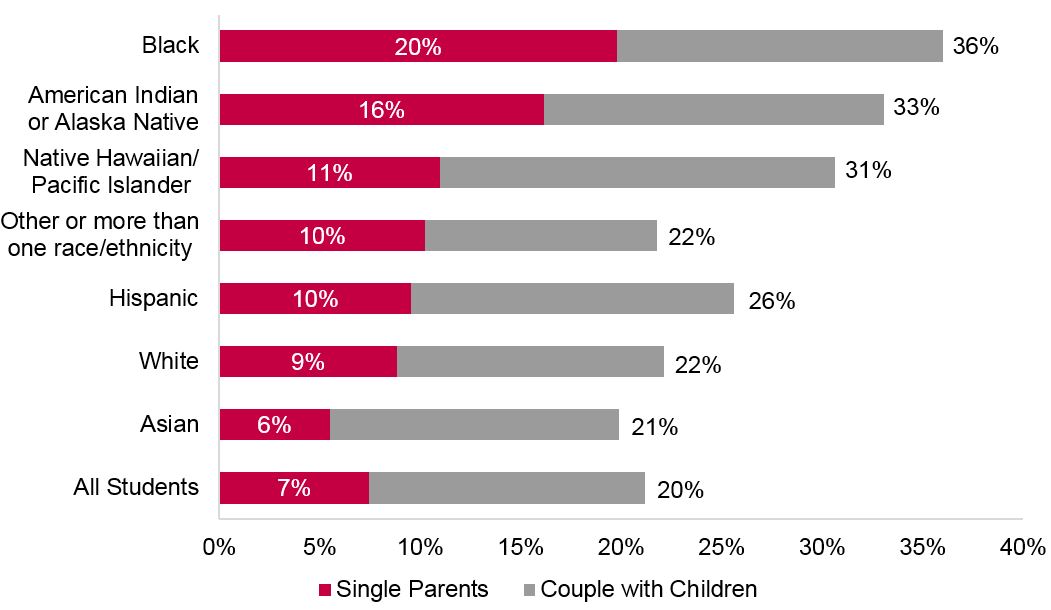

Addressing student parents’ child care needs in Washington is key to achieving racial/ethnic equity in access to postsecondary education. Approximately two-in-five student parents (38 percent) enrolled in Washington’s CTC system are students of color (IWPR 2017a). Black students are most likely to be parenting while attending community college (36 percent of all Black college students in Washington State are raising children), followed by American Indian/Alaska Native (33 percent) and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander students (31 percent), Hispanic (26 percent), and White (22 percent) students (Figure 1). Black student parents are also disproportionately likely to be single (55 percent), with single Black student parents representing 20 percent of all Black students enrolled in Washington CTCs. Sixteen percent of all American Indian/Alaska Native CTC students and 11 percent of all Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander CTC students in Washington State are parenting without the support of a spouse or partner (as are 9 and 10 percent of White and Hispanic CTC students, respectively; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Share of Washington State Career and Technical College Students who are Parents of Dependent Children, by Family Status and Race/Ethnicity, 2014-15

Note: Parent status is self-reported via online institutional admissions forms; “couple with children” refers to all parents who do not indicate that they are single parents. Source: IWPR analysis of data from the Washington State Board of Community and Technical Colleges, Data on Community and Technical College Students, 2014-15.

The Financial and Caregiving Demands Faced by Student Parents

Financial support is crucial for parents enrolled in community college, especially in the Far West region; 44 percent in the Far West region live with incomes at or below the federal poverty line, compared with 42 percent of student parents nationally (IWPR 2017b). Student parents represent more than one quarter (28 percent) of CTC students in Washington who receive financial aid (IWPR 2017a). This financial assistance, however, does not sufficiently cover many student parents’ college expenses: among students in Washington who receive a Pell grant, student mothers graduate with $2,500 more in debt than dependent students without children ($5,940 compared with $3,464 for dependent students; IWPR 2017a).

Caregiving demands affect student parents’ ability to devote the time needed to succeed in school. Nearly three-quarters of women community college students living with dependents (71 percent) report spending over 20 hours per week caring for dependents (half of fathers report the same). Many of these students report that care demands are likely to lead them to drop out: 43 percent of women and 37 percent of men at two-year institutions who live with children say they are likely or very likely to withdraw from college to care for dependents (IWPR 2017c).

Child care costs represent a large financial burden for parents who are in college. The annual cost of full-time, center-based infant care averages $13,110 in Washington, which would amount to half of the median state income for single parents (Child Care Aware of America 2017). Given the financial pressures experienced by student parents, both married and single, assistance with paying for quality child care services could dramatically improve their ability to make ends meet and complete their programs.

Though a large share of public two- and four-year institutions in Washington have campus child care centers (74 percent of all public institutions and 88 percent of community colleges in the state), many student parents still struggle to find and afford quality child care (Eckerson et al. 2016). Campus child care centers typically serve only a fraction of student parents on campus (Miller, Gault, and Thorman 2011). A recent IWPR study found that campus child care centers have a waiting list of 80 children on average (Noll forthcoming).

Washington State’s Child Care Assistance Rules Make it Difficult for Low-Income Students to Access Child Care

Washington has established particularly stringent eligibility rules for student parents to receive child care assistance (Washington House of Representatives 2014). Eligibility rules for the state’s Child Care Development Block Grant-funded Working Connections Child Care (WCCC) Program limit Washington parents’ access to affordable, quality child care. While recent changes have brought these rules into better alignment with the state’s ambitious goals for higher education, Washington must go further to ensure that its early childhood education policies support low-income students’ college attainment (National Women’s Law Center 2015; Washington Department of Early Learning 2016).[4]

Research suggests that child care helps parents persist in and complete higher education programs. A study at Monroe Community College (MCC) in New York found that MCC students with children under the age of six who used the campus child care center were more likely to return to school the following year than their counterparts who did not use the center (68 percent compared with 51 percent). Parents who used child care were also nearly 3 times more likely to graduate or go on to pursue a B.A. within 3 years of enrollment (41 percent compared with only 15 percent; Monroe Community College 2013).

Washington is one of 11 states that require parents in postsecondary education to also work to be eligible for child care assistance, which limits their ability to succeed in school (Eckerson et al. 2016; National Women’s Law Center 2015). To receive a child care subsidy, student parents are required to work at least 20 hours per week (or be in a paid federal or state work study program associated with education or training for at least 16 hours per week; Washington Department of Early Learning 2016). Washington is one of just three states that require student parents to work at least half-time to receive child care assistance (in addition to Arizona and Kentucky; Eckerson et al. 2016; National Women’s Law Center 2015).[5]

Work requirements for child care assistance can have negative consequences for parents in education or job training (IWPR 2017d). Students working more than 15 hours per week achieve significantly lower college attainment compared with those who work fewer hours. Nationally, 58 percent of community college student parents who work 15 or more hours per week leave school without earning a credential within six years of enrollment, compared with 48 percent who work less than 15 hours per week. This may be due, in part, to student parents electing to attend school part time when they are also working and raising children, which reduces students’ levels of college engagement and limits their chances to complete. Three in four student parents (74 percent) who enroll part-time in two-year programs fail to earn a credential (IWPR 2017d).

Child Care Assistance Eligibility Rules Prohibit Student Parents from Pursuing Transfer and Bachelor’s Degrees

To receive child care subsidies while in college, students in Washington State cannot be enrolled in bachelor’s degree programs or in community college programs designed to lead to transfers to four-year programs. Washington is one of only five states that restrict the type of degree that parents can pursue while receiving child care assistance to below a bachelor’s degree (National Women’s Law Center 2015). Parents are only eligible to receive child care assistance if they are pursuing a vocational degree or certificate that leads to a specific job or occupation at an approved technical or community college (Minton et al. 2015; Washington Department of Early Learning 2016).[6] No list of specific eligible degree programs exists, however, so students’ eligibility is based on the discretion of the case managers who review their subsidy applications. In addition, parents pursuing the Direct Transfer Agreement (DTA) associate’s degree, which facilitates students’ transfer from a two-year to a four-year college or university, are ineligible for subsidies (Judge 2015). DTAs include associate’s degrees in engineering, computer science, biology, nursing, and business, among others.

Student parents could be choosing lower quality degrees because of these subsidy eligibility requirements that affect their ability to receive child care assistance while in school. Among female CTC students with and without children who graduated in 2015, student mothers were more likely to earn a certificate or vocational degree (IWPR 2017a). They were less likely than non-mothers to earn an “academic associate degree,” which can be transferred to baccalaureate programs and possibly lead to higher paying jobs. Enrollment in these programs would render them ineligible for child care assistance under current state regulations.

Limiting child care assistance to those in a vocational degree or certificate program can jeopardize parents’ future earnings and financial security, in addition to their children’s future success. Higher levels of education are associated with higher lifetime earnings and higher rates of employment over the lifecycle (Carnevale, Rose, and Cheah 2011; Hartmann and Hayes 2013). In Washington, the median annual earnings of women with a bachelor’s degree working full-time, year-round are more than $10,000 higher than those of women with an associate’s degree (Hess and Milli 2015). Higher levels of education also have positive multigenerational effects. Research has found that a mothers’ educational attainment can have significant positive effects on her child’s educational outcomes and is a significant predictor of whether her child will attend college (Attewell and Lavin 2007).

Subsidy programs should be designed to help low-income parents prepare for the best-paying jobs possible to support the best possible financial outcomes for families, communities, and the states. Yet, Washington’s child care subsidy policy creates disincentives for pursuing degrees that provide the best chance of economic security.

Better Child Care Access Can Support Washington State’s Postsecondary Education Goals

Washington State passed legislation in 2014 that set goals to dramatically increase the number of adults with postsecondary credentials by 2023, but the state’s strict restrictions on child care assistance for college students threatens these postsecondary attainment goals. In 2013, the Washington Student Achievement Council (WSAC) released a 10-year strategic plan, called the Roadmap, outlining the state’s educational attainment goals: by 2023, all adults ages 25-44 in Washington will have a high school diploma or equivalent and at least 70 percent will have a postsecondary credential (Washington Student Achievement Council 2013). The Roadmap was adopted in early 2014 by Washington State House Bill ESHB 2626, signaling the legislature’s commitment to increasing degree attainment in the state (Washington House of Representatives 2014).

In the first Roadmap progress report, released in 2015, WSAC estimated that, to meet the 2023 goals, 360,000 more Washington adults would need to earn high school diplomas, and 500,000 more adults would need to complete a postsecondary credential by 2023 (Washington Student Achievement Council 2015). WSAC highlighted the need to focus on postsecondary recruitment, retention, and completion for traditionally underrepresented and underserved populations, including low-income students (Washington Student Achievement Council 2015). In its more recent 2017-2019 Strategic Action Plan, WSAC prioritized the expansion of investments in supports that can improve completion among underrepresented students, and the development of a plan to address the needs of working adult students—including child care and other family commitments—that can affect their ability to return to school and earn a college credential (Washington Student Achievement Council 2016).

The child care needs of student parents must be considered as Washington works to achieve its postsecondary milestones. Aligning Washington’s child care assistance rules with its goals for degree attainment would be an important first step. Eliminating work requirements for parenting college students, or counting hours spent in school as work, would help parents with the ambition to pursue a higher degree—be it vocational or baccalaureate—receive child care assistance. Helping parents afford child care has the potential to increase parents’ postsecondary attainment and contribute to building the workforce Washington needs to meet the demands of its growing economy.

References

Adams, Gina, Caroline Heller, Shayne Spaulding, and Teresa Derrick-Mills. 2014. Child Care Assistance for Parents in Education and Training: A Look at State CCDF Policy and Participation Data. Washington, DC: Urban Institute. <http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/alfresco/publication-pdfs/413254-Child-Care-Assistance-for-Parents-in-Education-and-Training.PDF> (accessed June 15, 2015).

Attewell, Paul and David Lavin. 2007. Passing the Torch: Does Higher Education for the Disadvantaged Pay Off Across the Generations? New York, NY: Russell Sage Publishers. <https://www.russellsage.org/publications/passing-torch> (accessed June 1, 2016).

Carnevale, Anthony P., Stephen J. Rose, and Ban Cheah. 2011. The College Payoff: Education, Occupations, Lifetime Earnings. Washington, DC: Georgetown University, Center on Education and the Workforce. <http://www2.ed.gov/policy/highered/reg/hearulemaking/2011/collegepayoff.pdf> (accessed July 31, 2014).

Child Care Aware of America. 2017. Parents and the High Cost of Child Care: 2016 Report. Arlington, VA: Child Care Aware of America. <http://usa.childcareaware.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/CCA_High_Cost_Report.pdf> (accessed January 17, 2017).

Eckerson, Eleanor, Lauren Talbourdet, Lindsey Reichlin, Mary Sykes, Elizabeth Noll, and Barbara Gault. 2016. “Child Care for Parents in College: A State-by-State Assessment.” Briefing Paper, IWPR #C445. Washington, DC: Institute for Women’s Policy Research. <https://iwpr.org/publications/pubs/child-care-for-parents-in-college-a-state-by-state-assessment/> (accessed December 21, 2016).

Hartmann, Heidi and Jeff Hayes. 2013. How Education Pays Off for Older Americans. Report, IWPR #C410. Washington, DC: Institute for Women’s Policy Research. <https://iwpr.org/publications/pubs/how-education-pays-off-for-older-americans> (accessed December 21, 2016).

Hess, Cynthia and Jessica Milli. 2015. The Status of Women in Washington: Forging Pathways to Leadership and Economic Opportunity. Report, IWPR #R381. Washington, DC: Institute for Women’s Policy Research. <https://iwpr.org/publications/the-status-of-women-in-washington-forging-pathways-to-leadership-and-economic-opportunity/> (accessed October 12, 2017).

Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR). 2017a. Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR) analysis of the Washington State Board of Community and Technical Colleges, Data on Community and Technical College Students, 2014-15.

———. 2017b. Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR) analysis of data from the U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2011–12 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS:12).

———. 2017c. IWPR analysis of data from the 2016 Community College Survey of Student Engagement (CCSSE) microdata.

———. 2017d. Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR) analysis of data from the U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2003–04 Beginning Postsecondary Students Longitudinal Study, Second Follow Up (BPS:04/09).

Judge, Matt. 2015. Email message from Matt Judge (Subsidy Policy Supervisor, Washington Department of Early Learning) to Casey Osborn-Hinman (Early Learning Advocacy Manager, Children’s Alliance). August 10, 2015.

Miller, Kevin, Barbara Gault, and Abby Thorman. 2011. Improving Child Care Access to Promote Postsecondary Success Among Low-Income Parents. Report, IWPR #C78. Washington, DC: Institute for Women’s Policy Research. <https://iwpr.org/publications/improving-child-care-access-to-promote-postsecondary-success-among-low-income-parents/> (accessed October 12, 2017).

Minton, Sarah, Kathryn Stevens, Lorraine Blatt, and Christin Durham. 2015. The CCDF Policies Database Book of Tables: Key Cross-State Variations in CCDF Policies as of October 1, 2014 (OPRE Report 2015-95). Washington, DC: The Urban Institute. <http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/opre/ccdf_policies_database_2014_book_of_tables_final_11_05_15_b508_3.pdf> (accessed January 20, 2016).

Monroe Community College. 2013. “Campus Child Care Center & Student Outcomes.” Inside IR 4 (2): 3. <http://www.monroecc.edu/depts/research/documents/Spring2013Newsletterfinal_000.pdf> (accessed October 12, 2017).

National Women’s Law Center. 2015. Building Pathways, Creating Roadblocks: State Child Care Assistance Policies for Parents in School. Washington, DC: National Women’s Law Center. <https://nwlc.org/resources/building-pathways-creating-roadblocks-state-child-care-assistance-policies-parents-school/> (accessed October 4, 2017).

Noll, Elizabeth. forthcoming. “Supporting Campus Children’s Centers: Findings from 2016 Campus Children’s Centers Leaders Survey.” Washington, DC: Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

Noll, Elizabeth, Lindsey Reichlin, and Barbara Gault. 2017. College Students with Children: National and Regional Profiles. Report, IWPR #451. Washington D.C.: Institute for Women’s Policy Research. <https://iwpr.org/publications/college-students-children-national-regional-profiles/> (accessed October 12, 2017).

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2016. “OCC Fact Sheet.” Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Child Care. <http://www.acf.hhs.gov/occ/fact-sheet-occ> (accessed August 25, 2016).

Washington Department of Early Learning. 2016. “Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) Plan for State/Territory Washington FFY 2016-2018.” <https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/occ/washington_stplan_pdf_2016.pdf> (accessed August 8, 2016).

Washington House of Representatives. 2014. House Bill Report ESHB 2626. Olympia, WA: Washington House of Representatives. <http://lawfilesext.leg.wa.gov/biennium/2013-14/Pdf/Bill%20Reports/House/2626-S.E%20HBR%20PL%2014.pdf> (accessed March 8, 2016).

Washington State Department of Social and Health Services, Economic Services Administration. 2016. “1.2 Required Participation | DSHS.” WorkFirst Handbook. <https://www.dshs.wa.gov/esa/chapter-1-engaging-parents-workfirst/12-required-participation> (accessed October 12, 2017).

Washington State Legislature. 2017. “Washington State Legislature.” Bill Information. SB 5975 – 2017-18: Relating to Paid Family and Medical Leave. July 10. <http://app.leg.wa.gov/billsummary?BillNumber=5975&Year=2017> (accessed July 10, 2017).

Washington Student Achievement Council. 2013. The Roadmap: A Plan to Increase Educational Attainment in Washington. Olympia, WA: Washington Student Achievement Council. <http://www.wsac.wa.gov/sites/default/files/2013RoadmapWeb.pdf> (accessed March 10, 2016).

———. 2015. 2015 Roadmap Report: Measuring Our Progress. Olympia, WA: Washington Student Achievement Council. <http://www.wsac.wa.gov/sites/default/files/2015.Roadmap.Report.pdf> (accessed March 9, 2016).

———. 2016. 2017-19 Strategic Action Plan. Olympia, WA: Washington Student Achievement Council. <http://www.wsac.wa.gov/sites/default/files/2016.12.01.SAP.pdf> (accessed October 26, 2017).

Women’s Funding Alliance envisions a world where all women and girls have the opportunity to live, lead and thrive. Our mission is to advance leadership and economic opportunity for women and girls in Washington State. We accomplish this by making the case, driving solutions and mobilizing people to make change. Visit www.wfalliance.org.

[1] The Far West Region is one of eight regional classifications used by the U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS), and includes the states of Alaska, California, Hawaii, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington.

[2] The Washington State Board of Community and Technical Colleges (SBCTC) collects data on students with dependent children through their admissions forms, allowing for unique state-level insight into the student parent population enrolled at Washington’s community and technical colleges. Comparable state-level data on student parents at four-year institutions in the state are not available. Regions are the smallest unit of analysis deemed representative by NPSAS sampling methodology, which is typically used to provide national profiles of parenting college students.

[3] Data from the SBCTC were collected by the Institute for Women’s Policy Research on behalf of the Women’s Funding Alliance in Seattle, WA. For more information on the Alliance’s work to improve the lives of women and girls in Washington State, visit www.wfalliance.org/.

[4] Washington’s 2016-18 Child Care Development Fund plan removed time limits on subsidy eligibility, allowing student parents to attend school at a pace and intensity of their choosing. Prior to 2016, student parents in Washington could receive assistance while pursuing a vocational program for a maximum of 36 months and parents enrolled in Adult Basic Education, English as a Second Language, or high school/GED courses could receive assistance for a maximum of 24 months (Minton et al. 2015). For more information, see Washington Department of Early Learning 2016.

[5] Students participating in WorkFirst, Washington’s temporary cash assistance program, and are over the age of 21, must fulfill separate requirements, which may include 20 work hours per week or hours spent in vocational education; WorkFirst recipients are guaranteed child care assistance (Washington State Department of Social and Health Services, Economic Services Administration 2016). Student parents participating in the Basic Food, Employment, and Training (BFET) program are also guaranteed access child care assistance, though they must not be enrolled in four-year degree programs or transfer degrees (Katz and Krauss 2014; Washington State Department of Social and Health Services, Economic Services Administration 2014).

[6] In February of 2017, a bill was introduced in the Washington State Senate (SB 5742) that would allow student parents who are pursuing baccalaureate degrees, but not participating in the WorkFirst program to be eligible to receive child care subsidies. It has been referred to committee (Washington State Legislature 2017).